쓰기 처리 과정에서 전두엽의 기능

Copyright 2024 ⓒ Korean Speech-Language & Hearing Association.

This is an Open-Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

초록

전두엽은 인간의 뇌에서 언어, 인지 및 운동 기능을 포함한 고등 인지 처리에 중요한 역할을 담당한다. 쓰기는 집행기능, 작업기억, 주의력 등과 더불어 언어 능력, 운동 계획 및 프로그래밍까지의 고차원적인 활동을 요구한다. 본 연구에서는 쓰기의 중추와 말초 처리 과정에서 전두엽의 역할을 살펴보고 실서증 양상과 관련지어 분석해보고자 한다.

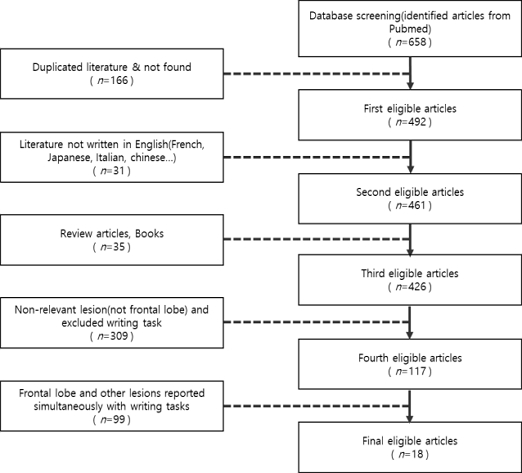

문헌 검색을 위해 ‘Pubmed’ 검색엔진을 활용하였으며, 1948년 1월 1일부터 2024년 4월 1일까지 ‘handwriting’, ‘agraphia’, ‘frontal’ 등의 키워드를 조합하여 검색하였다. 총 658편의 논문이 검색되었으며, 최종적으로 18편의 논문이 선택되었다.

총 18편의 문헌을 실서증 양상에 따라 분류하였으며, 중추적 단계에 해당하는 문헌 8편, 말초적 단계에 해당하는 문헌 9편, 중추 및 말초를 모두 포함하는 문헌 1편이었다. 중추적 단계에 해당하는 어휘실서증 1편, 음운실서증 5편, 어휘와 음운실서증을 모두 보고한 연구 1편, 그리고 심층실서증 2편이었다. 말초적 단계에 해당하는 이서 장애 3편, 실행실서증 5편, 공간실서증은 1편이었다.

전두엽의 손상은 어휘 및 음운 철자 처리와 운동 계획을 포함한 중추 및 말초적 단계 모두에 영향을 미치며 세부적인 병소에 따라 상이한 양상의 쓰기 장애로 나타났다. 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정에서 전두엽은 저장된 철자 정보를 표현하기 위한 어휘 선택 및 탐색, 그리고 음운 정보의 변환에 관여하며, 말초 처리 과정에서 철자에 대한 정보를 구체적인 글자의 형태로 산출하는 운동 계획으로 변환하는 기능을 담당한다. 본 연구 결과는 전두엽 손상으로 나타나는 쓰기 오류에 대한 양상 확인과 실서증에 대한 감별 진단 시 참고할 수 있는 기초 자료가 될 수 있다.

Abstract

The frontal lobe plays a crucial role in higher cognitive processing, encompassing language, cognitive, and motor functions. Writing requires complex cognitive processing such as executive function, working memory, and attention, as well as language, motor planning, and programming. This review investigates the roles of the frontal lobe in central and peripheral processes of writing.

The ‘Pubmed’ search engine was used to conduct a literature search using a combination of keywords such as ‘handwriting’, ‘agraphia’, and ‘frontal’ from 1948 to April 1, 2024. A total of 658 papers were searched and 18 were selected.

A total of 18 research papers were classified according to the pattern of agraphia, with 8 corresponding to the central, 9 corresponding to the peripheral process, and 1 corresponding to both. The research of central agraphia included 1 case of lexical, 5 phonological, 1 including both lexical and phonological agraphia, and 2 deep agraphia. There were 3 research papers on allographic, 5 apraxic, and 1 spatial agraphia, which correspond to the peripheral process.

Damage to the frontal lobe affects both the central and peripheral stages of writing processes, including lexical and phonological processing as well as motor planning, resulting in various types of writing disorders depending on the specific lesion. In the central process, the frontal lobe involved in lexical selection and retrieval for producing stored graphemic representation and in the conversion of phonological information. In the peripheral process, it is responsible for converting graphemic representation into motor plans that produce specific forms of letters. This study provides fundamental data that can be referenced for identifying patterns of writing errors caused by frontal lobe damage and for differential diagnosis of agraphia.

Keywords:

Frontal lobe, agraphia, writing, spelling키워드:

전두엽, 실서증, 쓰기, 철자Ⅰ. 서론

전두엽은 인간의 뇌에서 약 3분의 2를 차지하는 가장 넓은 영역으로, 주로 운동, 언어 및 다양한 인지 기능을 담당한다(Chayer & Freedman, 2001). 전두엽의 운동기능과 관련하여 일차운동영역(brodmann area 4: BA 4)은 인체의 복잡한 수의적 움직임을 집행하며, 전운동영역(BA 6)은 순차적인 수의적 운동을 계획하고 운동과 관련된 심상을 발생시켜 지각한 감각 자극과 적절한 운동 사이의 전환에 관여한다. 전두엽의 가장 앞쪽을 차지하며 내측, 복측, 배외측 등의 영역을 구성하는 전전두 피질(prefrontal cortex)은 집행기능과 작업기억 능력과 같은 넓은 범위의 고등 인지 기능을 담당한다. 이 중에서 내측 전전두 피질(medial prefrontal cortex)은 BA 9~12 및 BA 25, 전대상 피질(anterior cingulate cortex)인 BA 24, BA 32를 포함하며 주로 의지, 주의력 및 인지적 자원을 처리하고, 내부적 동기 또는 상태에 기반한 활동을 선택한다. 복측 전전두 피질(ventral prefrontal cortex)은 안와전두 피질(orbitofrontal cortex)의 BA 11과 BA 13에 해당하며, 충동 조절, 강박 행동, 정서적 의사 결정 그리고 연역적 추론 과정에 관여한다. 배외측 전전두 피질(dorsolateral prefrontal cortex)은 BA 8~10, BA 46을 포함하며 행동, 인지 및 언어영역에서 목표 지향적으로 조직화하는 능력인 집행기능을 담당하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 이처럼 전두엽의 앞쪽 영역들은 여러 인지적인 처리에 필수적이며 언어나 의사소통의 이해와 사용에 대한 해석을 제공하기도 한다.

배외측 전전두 피질에서 뒤쪽 아래 부위에 해당하는 복외측 전전두 피질(ventrolateral prefrontal cortex)은 BA 45와 인근의 BA 44를 포함한다. 좌측의 경우 뒤쪽 하전두엽(left posterior, inferior frontal lobe)은 일명 ‘브로카 영역(broca’s area)’로 불리며 말 또는 언어 산출의 중추로 언어 기능과 더욱 직결된다(Carlson, 2007). 이 영역은 문장의 어순 처리와 같은 문법형태소의 사용이나 언어의 산출뿐만 아니라 구문구조의 구성적 측면에서 언어를 이해하는 것에도 관여한다(Swinney et al., 2000; Zurif & Swinney, 1994). 그간 전두엽이 인지나 언어 처리 과정에 기여하는 역할은 병소의 영향을 증명하는 뇌영상기법을 활용한 연구에서 확인되었다. 그리고 개인이 갖는 뇌의 형태나 크기의 차이가 있음에도 불구하고, 좌측 뒤쪽 하전두엽이나 뒤쪽 상전두엽과 같은 전두엽의 특정한 영역들은 다양한 언어 과제에서 일관된 결과를 보여주었다. 보다 최근에는 좌측 뒤쪽 하전두엽, 전대상 피질, 그리고 보조운동영역으로 구성된 말 산출 회로의 차단이 비유창형 원발성 진행성 실어증(nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia: nfvPPA)과 같은 퇴행성 언어장애의 병인으로 보고되었다(Catani et al., 2013). 좌측 뒤쪽 하전두엽 병소는 비문법적인 발화 산출의 결과를 초래하는데, 이는 내용어 위주의 단어들과 기능어나 접사 등의 문법형태소가 생략된 ‘전보문식(telegraphic)’ 발화의 형태로 드러난다. 전보문식 발화는 더 짧은 문장과 단순한 통사 구조를 포함하며(Miceli et al., 1989; Thompson et al., 2015), 문장을 구성하는 기능적 단계에서의 결함(Caramazza & Miceli, 1991; Martin & Blossom-Stach, 1986), 어휘 접근, 또는 제한된 작업기억으로 인한 문장의 표상을 유지하는 능력의 결함으로 해석될 수 있다(Linebarger et al., 2000).

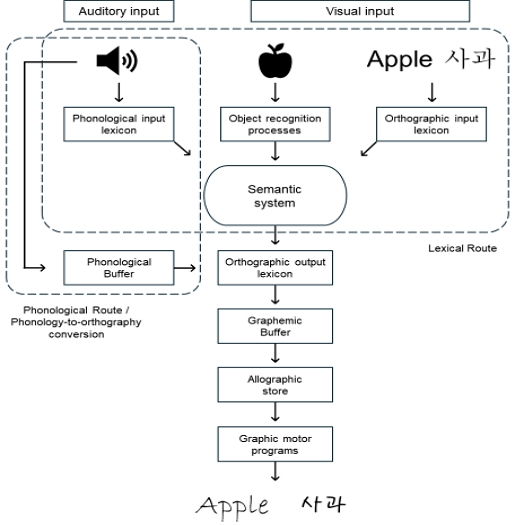

위와 같이 전두엽은 구어(verbal language)뿐만 아니라 문어(written language)를 해석하고 계획하여 산출하는 행위에 이르기까지 다양한 언어적 활동에 전반적으로 관여한다(Purcell et al., 2011). 문어 능력 중 특히 쓰기의 경우 복잡한 신경심리학적 기제의 처리 과정에 기반을 두고 있다. 이러한 처리 과정에 초점을 둔 쓰기 모델(Roeltgen & Heilman, 1985)에서 제시한 각 단계의 과정을 살펴보면, 먼저 철자 지식을 활성화하는 단계가 필요한데, 이는 크게 어휘 경로와 음운 경로로 이루어져 있다. 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정(Patterson, 1986)이라 불리는 이 과정에서는 단어의 철자적 특성에 따라 두 가지 경로 중 하나를 주로 활용된다. 어휘 경로는 시각 혹은 청각적으로 제시된 자극을 분석하여 내부철자사전(internal spelling dictionary) 또는 철자어휘집(orthographic lexicon)에 저장된 단어의 자소 표상을 얻게 되므로 음소-자소 간의 불일치성이나 모호성에 상관없이 의미어휘체계를 활성화하여 저장된 단어의 의미를 연상하고 철자를 처리한다. 반면, 음운 경로는 제시된 자극이 저장되지 않은 단어인 비단어 또는 처음 접하는 단어인 경우 오로지 음소에 의존하여 대응되는 자소를 선택하고 처리한다. 중추 처리 과정 이후 쓰기의 실제 수행 단계로 넘어가기 전에는 자소-버퍼 단계를 거치는데 이때는 중추 처리에서 활성화된 단어를 임시적으로 저장한다. 저장된 철자의 표상은 글자나 단어로 산출되기 위해 말초 처리 과정을 거치게 되는데, 먼저 글자를 통합하고 글자의 형태를 정하기 위해 이서 단계로 가게 된다. 이어서 형태가 정해진 글자의 모양을 산출해내기 위한 쓰기 운동의 계획 및 프로그래밍의 단계에서는 글자의 크기나 획의 순서 및 방향을 결정하고, 시공간의 인식이나 방향감에 대한 능력과 상호작용하면서 최종적으로 운동 집행을 위해 필요한 사지에 명령을 전달한다.

즉, 글씨를 쓰는 과정은 철자를 처리하는 다양한 경로를 통해 선택된 추상적인 정보가 물리적인 형태로 구현되기 위해 철자 형태에 대한 표상과 더불어 철자의 형태를 산출하기 위한 운동 계획 및 프로그래밍과 운동 집행 단계에서 획의 방향이나 공간적 표상을 처리한다. 동시에 작업기억, 주의력, 집행기능 등의 다양한 인지 처리 과정과도 면밀히 상호작용한다. 집행기능이나 작업기억과 같은 인지 처리 과정을 주로 담당하는 전두엽은 다른 엽과 비교하여 가장 늦게 발달이 이루어지는 것으로 알려져 있다(Romine & Reynolds, 2004). 따라서 상기에 언급한 인지, 언어, 운동 능력 간의 복합적 관계의 산물에 해당하는 쓰기 능력은 구어 능력과 비교하여 명시적 학습에 더 의존하면서 더 늦은 시기에 습득되는(Hagtvet, 1993), 전두엽의 고등한 인지 처리 기능을 반영하는 하나의 지표가 될 수 있다.

전두엽은 쓰기 처리 과정의 전반에 걸쳐 영향을 미칠 수 있으나 그간 중추 처리 과정을 다루는 대다수의 연구는 주로 어휘 및 음운 처리에 있어서의 좌측 측두엽과 두정엽의 역할에 초점이 맞추어져 있었다(Alexander et al., 1992; Maeshima et al., 2003; Tohgi et al., 1995). 전두엽의 경우, 쓰기와 관련된 역할은 주로 말초 처리 과정의 일부 단계에 국한되어 논의되었다. 이에 쓰기에서의 중추 처리 과정과 말초 처리 과정에 모두 관여할 수 있는 전두엽의 포괄적인 역할과 기능을 탐색하고 고찰한 연구는 국내외를 막론하고 찾아보기 힘든 실정이다. 특히 쓰기 처리와 같은 고차원적이고 복잡한 인지 과정을 고찰하기 위해서는 특정 뇌 영역의 역할을 바탕으로 뇌 영역 간의 통합적 네트워크를 포괄할 필요가 있으므로 측두엽이나 두정엽과 더불어 전두엽의 역할 또한 이해할 필요가 있다. 이러한 맥락에서 전두엽의 병소를 보고한 국소 병변 연구(focal lesion study)는 타 영역과 구별되는 전두엽의 기능과 역할에 대한 통찰력을 제공한다. 본 고에서는 전두엽 손상을 특정하거나 포함한 실서증 연구들에 대한 체계적인 문헌 분석을 통하여 전두엽의 언어, 인지, 운동적 기능이 중추부터 말초 단계까지 이르는 쓰기의 처리 과정에서 각각 어떠한 역할을 하는지 살펴보고, 통합적 측면에서의 전두엽의 역할을 고찰해보고자 한다.

Ⅱ. 연구 방법

1. 문헌 검색

본 연구는 전두엽의 손상으로 인한 양상을 알아보기 위해 의학과 관련하여 폭넓은 MEDLINE 데이터베이스에 접근할 수 있는 미국 국립 의학 도서관의 검색 엔진(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)을 이용하였다. 데이터베이스의 검색 시, 검색어의 수식 기능을 활용하여 발달성 쓰기 장애를 제외하였으며, 전두엽의 병변을 포함한 모든 문헌을 도출할 수 있는 검색어 설정이 어렵다는 점을 고려하여 쓰기와 관련한 모든 실서증 문헌을 검색어에 포함되도록 하였다. 검색어는((spelling OR handwriting OR writing) (agraphia OR dysgraphia)) OR (frontal, (agraphia OR dysgraphia)) NOT (student OR child*)이었으며, 이를 통해 1948년 1월 1일부터 2024년 4월 1일 사이에 해당하는 총 658편의 연구가 검색되었다.

2. 문헌 선정

수집된 658편의 연구 중 전두엽의 손상을 보고하며 쓰기 과제를 통해 환자의 쓰기 능력을 확인한 연구를 추출하기 위해 다음과 같은 제외 기준을 적용하였다. 첫째, 열람이 불가능하거나 중복된 연구를 제외하였다. 둘째, 열람이 가능한 연구 중 본문이 영문으로 작성되지 않은 연구를 제외하였다. 셋째, 문헌 연구나 책의 챕터 형식으로 출판된 경우를 제외하였다. 마지막으로 전두엽과 무관한 병소만을 보고하거나 쓰기 과제가 포함되지 않아 실서증 양상의 분류가 불가능한 연구를 제외하였다. 상기의 기준에 따라 총 117편의 문헌이 최종 분석 대상으로 선정되었으며, 이 중에서 전두엽 단독의 병변을 보고한 연구는 18편에 해당하였다(Figure 1).

3. 분석 방법

본 연구에서는 선정된 문헌들을 인지적 정보 처리 과정에 기반하여 철자 및 쓰기운동의 과정을 설명할 때 널리 사용되는 쓰기 처리 모델(Beeson et al., 2002)에 기반하여 분석하였다. 분석 시, 각 단계에 따라 나타날 수 있는 결함에 대해 실서증의 하위 유형으로 나누어 세부적으로 분류하였다. 그리고 각 하위 유형에 따라 주로 보고되는 전두엽 내의 구체적인 병소와 해당 영역의 기능 및 역할에 대해 고찰하였다(Figure 2).

Ⅲ. 연구 결과

1. 연도별 출판 편수

전두엽 병소를 포함한 실서증 연구의 경향을 살펴보기 위하여 최종적으로 선정된 117편의 문헌을 10년 단위로 나누어 출판 편수를 확인하였다. 그 결과, 1970년에 보고된 1편의 문헌을 기점으로 1970년대 3편(9.4%), 1980년대 9편(34.2%), 1990년대 24편(20.5%), 2000년대 30편(25.6%), 2010년대 40편(34.2%), 그리고 2024년 4월 1일까지 집계된 문헌까지 포함하여 2020년대에 11편(9.4%)이 보고되었다.

2. 전두엽 단독 병변의 문헌

병변을 보고하는 병소 연구는 타 영역과 구별되는 특정 뇌의 영역에 대한 기능과 역할을 확인하는 데 용이하다. 이에, 최종적으로 선정된 117편의 문헌 중, 전두엽의 단독 손상을 보고한 18편의 문헌에 초점을 맞추어 보고된 대상자의 배경정보, 병인, 병소의 위치, 그리고 실서증의 유형에 따라 분류하였다(Appendix 1).

연구 구성의 측면에서 18편의 문헌 중, 1편은 중심고랑(central sulcus)을 기준으로 고랑의 앞쪽 병변 환자와 뒤쪽 병변 환자로 나눈 비교 연구(comparative study)였고, 그 외 17편은 전부 3명 이하의 전두엽 병변 대상자를 보고한 사례 연구(case study)로, 2편의 연구는 동일한 환자를 대상으로 하였다. 연도별 분석에 따르면, 1990년대 7편(38.9%), 2000년대 3편(16.7%), 2010년대 7편(38.9%), 2020년대 1편(5.6%)의 연구가 보고되었다.

1편의 집단 비교 연구와 중복 사례의 연구를 제외한 16편의 전두엽 단독 병변 연구의 대상자들은 모두 남성 10명과 여성 10명으로 총 20명이었으며, 이들의 평균 연령은 57세, 그리고 1명의 왼손잡이 환자 외에는 전부 오른손잡이였다. 병인론적 측면에서 진단명이 공개되지 않은 1편의 연구를 제외한 총 19명은 뇌졸중, 경색, 출혈 등으로 인한 혈관성 질환 14명, 성상세포종, 전이성 선암종과 뇌종양을 포함한 종양성 질환 3명, 외상성 뇌손상 1명, 그리고 지주막 낭종 1명이었다.

실서증 유형이나 쓰기 과제를 통해 확인된 처리 과정 측면에서의 결함을 기준으로 철자에 대한 인지 정보 처리 모델에 따라 분류를 하였을 때, 중추 처리 과정의 결함에 해당하는 문헌이 8편, 말초 처리 과정에 해당하는 문헌이 9편, 그리고 중추와 말초 처리 과정에 모두 해당하는 문헌이 1편으로 분석되었다. 이중, 중추 처리 과정으로 분류된 문헌의 구성은 어휘실서증 1편, 음운실서증 5편, 어휘실서증과 음운실서증 환자를 각각 보고한 연구 1편, 그리고 심층실서증 2편이었다. 말초 처리 과정으로 분류된 문헌의 구성은 이서 장애 3편, 실행실서증 6편, 공간실서증 1편이었다.

Ⅳ. 논의 및 결론

Roeltgen과 Heilman(1985)은 기존의 모델에서와 마찬가지로 철자의 선택이나 보유와 관련된 인지-언어적 처리 과정을 쓰기의 중추 처리라 하고, 이후의 철자의 운동 계획이나 운동 집행 과정을 쓰기의 말초 처리로 다루되, 처리 과정 내에 포함되는 하위 단계들을 신경심리학적인 기제와 관련지어 설명하면서 실서증의 양상을 분류하였다. 그간 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정에서 일반적인 신경학적 손상은 주로 측두엽을 중심으로 다루어졌으며, 전두엽의 손상은 말초 처리 과정에서 다루어졌다. 그러나 전두엽은 인지 및 운동기능과 더불어 언어기능까지 광범위한 기능을 담당하고 있으므로 쓰기에 있어서 말초 처리 과정뿐만 아니라 중추 처리 과정에도 관여할 수 있다.

1. 중추 처리 과정

단어를 구성하는 철자의 표상은 일반적으로 어휘 경로와 음운 경로로부터 의미와 음운 정보를 조합하여 활성화된다. 이러한 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정에서 전두엽은 다른 피질 영역들과 연결되어 해당 정보를 처리한다. 예를 들어, 좌측 후전두엽과 하전두엽 피질은 동사, 명사와 같은 품사별 어휘의 인출뿐만 아니라 철자 처리에 중요한 역할을 담당한다(González-Fernández & Hillis, 2018). 여기서는 어휘 및 음운 경로의 결함으로 발생하는 실서증 양상을 전두엽의 기능과 연관지어 살펴보았다.

어휘 경로는 단어의 시각적인 심상을 포함하여 통단어로 인출하는 과정을 거친다(Rapcsak et al., 1989). 의미적으로 친숙한 단어를 인출하기 위해서는 어휘 경로에서의 철자어휘집에 대한 접근이 필수적이며, 이러한 단어에는 자소와 음소가 불일치하는 불규칙단어가 포함된다. 어휘체계의 손상으로 쓰기의 어려움이 발생하는 어휘실서증 환자는 상대적으로 보존된 음운 경로를 통해 철자 처리를 수행하게 된다. 그간의 어휘실서증 환자들은 대부분 우세 반구의 측두-두정 접합부(temporo-parietal junction), 즉 뒤쪽 중/하측두이랑(BA 37) 혹은 각이랑(BA 39) 병변을 보였다(Roeltgen & Heilman, 1984). 이렇게 측두-두정 접합부 병변의 환자들은 어휘 경로가 손상되어 철자 표상에 대한 접근이 어려워지면서 일반적으로 쓰기 뿐만 아니라 읽기에서도 능력이 저하되는 양상을 보였다. 또한, 비단어에 비해 친숙했던 단어의 철자를 인출하지 못하며, 고빈도 단어에 비해 저빈도 단어의 쓰기가 어려운 양상을 보였다(Beauvois & Dérouesné, 1981; Hatfield & Patterson, 1983; Roeltgen & Heilman, 1984; Roeltgen & Rapcsak, 1993).

그러나 선행 연구에서는 측두-두정엽과 더불어 우측이나 좌측 후두엽, 좌측 미상핵과 시상을 포함한 다양한 병소도 함께 보고되었으므로 어휘실서증과 관련된 영역을 측두-두정엽으로만 단정 짓기는 어려울 수 있다(Croisile et al., 1989; Roeltgen & Heilman, 1984; Roeltgen & Rapcsak, 1993; Rothi et al., 1987). 특히, 좌측 후전두엽(BA 44, 45, 6) 혹은 중심앞이랑(precentral gyrus) 병변으로 인한 어휘실서증이 보고되면서, 중추 처리 과정에서 전두엽의 고유한 역할이 대두되었다(Hillis et al., 2004; Rapcsak et al., 1988; Sakurai et al., 1997). Hillis 등(2004)은 좌측 후전두엽(BA 44, 45, 6)에만 국한된 병변을 3명의 환자가 모두 보존된 이름대기와 읽기 수행을 보이며, 문어 중 쓰기 능력에 국한된 순수 어휘실서증(pure lexical agraphia) 양상을 보였다고 보고하였다. 일반적으로 알려진 측두-두정엽(BA 37, 39)영역은 어휘 처리 과정의 전반에 관여한다. 측두-두정엽 영역의 병변은 철자어휘집에 접근하는 단계에서 입력(읽기)과 출력(쓰기)에 모두 영향을 주며, 더불어 이름대기와 같은 언어 능력에도 영향을 미친다. 반면, 후전두엽의 BA 44와 45영역은 글자를 쓰기 위한 철자 표상을 운동 계획으로 변환하는 과정의 마지막 단계를 처리한다. 따라서 전두엽에 병변이 국한된 순수 어휘실서증을 보인 환자의 사례는 좌측 후전두엽이 쓰기 출력에 한정된 어휘 철자 표상으로의 접근과 처리에 관여한다는 것을 의미한다(Hillis et al., 2004). 그리고 명사와 비교하여 동사의 철자쓰기를 더 어려워하는 결과에 대하여 BA 44와 45는 접두사나 접미사와 같은 구체적인 형태적 변화에 대한 요소가 더해지는 동사 어휘(예, run-running-runs)의 철자 표상을 출력하는 것에서 특히 주요한 기능을 담당한다고 보고하였다. 어근에 접두사나 접미사와 같은 형태적 요소가 더해지는 동사는 명사와 비교하여 복잡한 단어 구조를 특정하고 선택하는 작업이 요구된다(Shapiro et al., 2001). 이러한 사례들은 전두엽의 역할이 쓰기의 말초 처리 과정에 국한되지 않는다는 점을 강조하고 있다.

전두엽의 병소로 국한된 실서증 양상은 영어 이외의 언어권에서도 나타났다. Sakurai 등(1997)은 음소와 자소가 대응하는 형태의 표음문자(phonogram)인 ‘가나(Kana)’와 음소와 자소가 대응하지 않는 표의문자(ideogram)인 ‘간지(Kanji)’ 쓰기에서의 수행력 해리(dissociation)를 보이는 두 명의 일어권 환자 사례를 비교하였다. 저자들은 한자에 기반을 두는 간지 문자로 이루어지는 단어는 상황에 따라 다양한 소리로 실현되므로 불규칙단어의 가장 극단적인 형태에 속한다고 주장하면서(Sakurai et al., 1997), 가나와 비교하여 간지의 수행력이 저하되는 환자의 병변이 중전두이랑의 가장 뒷부분과 그 부분에 인접한 중심앞이랑에 국소적으로 위치하였음에 주목하였다. 따라서 간지 쓰기의 오류는 통단어로 인식되는 단어의 시각적인 심상이 저장되어 있는 뒤쪽 하측두엽으로부터 각이랑과 상두정소엽을 통해 전두엽의 중전두이랑에 도달하는 어휘 경로의 결함에 기인한 것임을 주장하면서 전두엽이 어휘 경로의 처리 과정에 있어서 기존에 보고되던 영역들과 더불어 중요한 역할을 차지함을 역설하였다.

철자를 산출하기 위해 사용되는 다른 하나의 경로는 음운 경로로, 단어나 말소리를 음운적으로 해석하거나 음운적인 요소들을 각각의 대응되는 글자로 변환하는 과정을 포함한다. 이는 주로 일반적인 발음 규칙을 따르며 자소와 음소가 일치하는 규칙단어나 친숙하지 않은 단어인 비단어(nonword)를 떠올리는 데 관여한다. 음운 경로의 손상으로 인한 음운실서증(phonological agraphia)의 경우, 어휘 경로에 의존하여 철자어휘집에 저장되어 있는 단어의 쓰기는 가능하나 저장되어있지 않은 비단어는 음운적으로 연관된 실제 단어로 대체하는 오류인 어휘화 오류를 보이게 된다. 흔히 모서리위이랑(supramarginal gyrus)과 뇌섬(insula)을 포함한 뒤쪽 실비우스열 주위(posterior perisylvian) 영역은 음운실서증과 음운실독증을 유발하는 병소로 보고되며, 읽기와 철자대기에 대한 음운 처리의 기전으로 여겨졌다(Alexander et al., 1992; Bub & Kertesz, 1982; Nolan & Caramazza, 1982; Shallice, 1981).

그러나, 이어서 등장한 사례들은 뒤쪽 실비우스열 주위 영역들이 아닌 좌측 하전두엽, 중심앞이랑, 또는 중전두이랑 등의 보다 넓고 다양한 전두엽에 국한된 병변으로부터 보고되어, 음운 처리와 관련된 신경 네트워크가 앞쪽 실비우스열 주위에도 광범위하게 분포되어 있을 가능성을 시사하였다(Abe & Yokoyama, 1994; Keller & Meister, 2014; Levy et al., 2023; Sakurai et al., 1997, 2018; Tohgi et al., 1995). 일어권의 연구들(Abe & Yokoyama, 1994; Sakurai et al, 1997; Tohgi et al., 1995)에서도 간지에 비해 가나의 수행력이 저하되는 환자가 좌측 중전두이랑, BA 6, 8과 뒤쪽 BA 9, 중전두이랑의 후방 2/3영역의 병소를 가지고 있음을 보고하였다. 특히, Sakurai 등(2018)은 하전두엽에 위치한 덮개 영역이 활꼴 다발(arcuate fasciculus)의 종착지로, 일련의 단어나 음절의 음운론적 정보가 베르니케 영역으로부터 모서리위이랑을 통해 전두엽으로 전달된다고 주장하였다. 기능적 영상 연구들에 따르면, 브로카 영역에 해당하는 뒤쪽 하전두엽의 BA 44와 45는 음운-철자 변환과정에서 정확한 음소를 찾아내거나(Burton et al., 2000), 음소를 구별하는 역할(Démonet et al., 1994; Zatorre et al., 1992, 1996)을 담당하는 것으로 보고되는데, 이는 쓰기 처리 과정에서의 음운 경로와 전두엽의 관계를 지지한다.

한편, 비단어의 읽기는 정상적인 수행이 가능하나, 비단어의 쓰기에 결함을 보인 순수 음운실서증의 사례(Marien et al., 2001)를 통해 쓰기 처리 과정에 특정된 음운 체계가 앞쪽 뇌섬과 인접한 전두엽의 덮개 영역에 위치한다고 주장되었다. 이러한 양상은 좌측 중전두이랑의 병소 사례(Tohgi et al., 1995)에서도 보고되어, 적어도 다른 언어적 양식으로부터 분리된 쓰기의 음운 처리 체계에 전두엽이 관여한다는 것을 보여준다.

내부철자사전 내의 어휘에 대한 철자 표상을 올바르게 선택하기 위해서는 어휘 경로와 음운 경로의 적절한 상호작용이 이루어져야 한다(Hillis et al., 1999). 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정에서 어휘 및 음운-철자 변환 체계의 부분적인 손상은 보존된 경로 중 어떠한 경로에 더 의존하는가에 따라 상이한 오류 양상을 야기한다. 철자 처리의 두 경로가 모두 손상되어 음운적 능력과 내부 철자 사전에 모두 영향을 받는 심층실서증(deep agraphia) 환자는 손상이 있는 어휘 경로에 보다 의존하는 경향을 보이면서 의미적인 오류를 보일 수 있다. 이들은 내용어보다 기능어에서, 구체적 개념보다 추상적 개념에서, 그리고 고빈도 단어보다 저빈도 단어에서 빈번한 오류를 보인다. 또한 음운실서증과 마찬가지로 어휘화 오류도 보일 수 있다. 이러한 양상의 사례들은 대부분 음운실서증을 유발하는 모서리위이랑과 뇌섬으로부터 더욱 확장된 영역의 병변에서 보고된다(Bub & Kertesz, 1982; Nolan & Caramazza, 1982).

전두엽 병변의 사례로는 중전두이랑을 포함한 넓은 영역의 대사 저하, 그리고 전운동영역 주위 또는 브로카영역, 전두덮개, 기저핵에 혈류를 공급하는 중대뇌동맥(MCA)에 발생한 경색으로 인한 심층실서증 환자가 보고되기도 하였다(Bormann et al., 2008; Hillis et al., 1999; Utianski et al., 2018). 전두엽에 병변이 국한된 심층실서증 환자들은 상대적으로 구어 이름대기 능력이 보존되며 다양한 어휘처리 과제에서 온전한 이해력을 보이나, 서면 이름대기에서 의미적인 오류를 보이며, 손상된 어휘-의미 처리 과정으로 인해 단어의 마지막 글자가 생략되는 부분적인 철자 오류가 나타난다(Bormann et al., 2008).

자소-버퍼 장애(graphemic buffer impairment)는 중추 단계에서 음소를 자소로 변환하여 일시적으로 저장된 글자의 표상이 말초 단계로 이행하는 과정에서 소실되어 나타나는 오류로 중추와 말초 처리 과정 사이에 발생할 수 있는 실서증 하위 유형이다. 자소-버퍼는 철자 처리가 이루어지는 과정에서 자소의 표상을 일시적으로 활성화하는 작업기억의 영향을 받는다(Caramazza et al., 1987). 작업기억은 그룹화를 통해 기억해야 하는 항목의 수를 줄임으로써 작업기억 정보를 효율적으로 유지하는데, Baddeley(2000)의 작업기억 모델의 요인(factor) 중 음운루프는 제한 시간 내에 한정된 양의 구어 정보를 유지하는 시스템을 담당하고 있다. 임상에서 흔히 활용되는 쓰기의 과제 중 받아쓰기는 구어로 입력된 자극을 기억하고 유지하면서 철자 규칙에 맞게 산출하는 과제이므로, 쓰기 집행을 위한 운동 양식으로 전환되기 전 일시적으로 정보가 유지되어야 한다. 입력된 정보의 유지 과정은 작업기억 용량에 영향을 받는데 용량이 적은 사람일수록 일시적으로 정보를 유지하는 과정에서 정보의 소실이 빠르게 일어난다. 즉, 쓰기에서 작업기억의 한계는 자극의 길이가 길어지거나 복잡한 자극에 대한 정보 유지와 관리에 어려움을 유발할 수 있다.

그간 자소-버퍼 장애는 좌측 전두두정 영역, 그리고 우측 전두두정과 기저핵 영역 등의 다양한 병소로부터 보고되었다(Hillis & Caramazza, 1989; Lesser, 1990). 일반적으로 자소-버퍼에 국한된 쓰기 장애를 보인 사례들은 특정 병소에 국한되지 않고 좌측 전두엽, 두정엽, 그리고 일부는 측두엽 혹은 후두엽과 기저핵 병변이 포함된 광범위한 뇌졸중 환자들이 주를 이루었다(Caramazza et al., 1987; Cloutman et al., 2009; Tainturier & Rapp, 2004). 본고에서 살펴본 전두엽 병변을 포함한 자소-버퍼 장애의 사례들은 대부분 측두엽이 포함된 전두측두 영역(Code et al., 2017; Piccirilli et al., 1992; Posteraro et al., 1988), 또는 피질하 영역을 포함한 좌측 전두-피질하 영역을 보고하였다(Cubelli, 1991). 최근의 연구는 우측 안와전두피질에서 미상핵까지 확장된 병소의 자소-버퍼 장애를 보고하기도 하였다(Arroyo-Anlló et al., 2023). 자소-버퍼 단계에 관여하는 피질하 경로의 역할은 명확하지 않으나, 전전두피질의 경우, 피질-피질하 영역과 고리를 형성하면서 작업기억 체계에 중요한 역할을 한다(Cloutman et al., 2009; Deldar et al., 2021). 또한, 좌측 상전두이랑의 경우 단어 길이 효과에 관여하는 것으로 보고되었다(Rapp & Dufor, 2011). 이렇듯 작업기억 처리와 관련된 자소-버퍼 단계에서는 전두엽 손상에 국한된 경우보다 다른 영역과 동시적인 손상이 주로 보고되었다. 작업기억은 전두엽과 주변 다른 영역으로부터 시각, 청각 등의 감각 정보를 전달받아 처리되는 기능이기 때문에 전두엽과 더불어 여러 영역과 함께 보고가 이루어진 것으로 생각된다(Rapp & Dufor, 2011).

본 연구에서 살펴본 문헌의 자소-버퍼 장애의 양상은 일반적으로 다음과 같다. 첫째, 단어의 위치적 측면에서 오류를 보이는데 단어의 앞글자보다 중앙으로 갈수록 오류 빈도가 빈번한 모습을 보이게 된다(Luzzi & Piccirilli, 2003; Piccirilli et al., 1992). 둘째, 단어의 길이적 측면에서 오류를 보일 수 있게 된다. 단어 내 음절 길이, 철자의 길이가 증가할수록 오류가 증가하게 되는 양상이 나타난다(Code et al., 2017; Posteraro et al., 1988). 셋째, 단어 혹은 비단어 여부와 상관없이 자소 치환, 생략, 대치와 같은 철자 오류(graphemic error)를 보이게 된다(Croisile et al., 1990; Maeda et al., 2015; Miceli et al., 1997). 마지막으로, 단어의 빈도, 품사, 그리고 추상성과 같은 어휘적인 요인은 쓰기의 수행에 영향을 미치지 않는다(Arroyo-Anlló et al., 2023; Piccirilli et al., 1992; Posteraro et al., 1988). 즉, 더 많은 인지 자원이 요구되는 단어가 자소-버퍼 단계에 보관될수록 철자의 정확도는 떨어지며, 이는 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정 내에서 어휘 및 음운 경로와는 별개의 체계로 자리함을 시사한다.

2. 말초 처리 과정

철자 처리 과정을 수행하여 형성된 표상은 적절한 운동 능력을 통해 물리적인 글자의 형태로 산출된다. 그러나 적절한 운동의 프로그래밍이나 움직임 조절에 실패하게 된다면 말초형 실서증 양상을 보일 수 있다. 일반적으로 좌측 전두엽의 병변은 쓰기의 말초적인 측면과 관련되는데, 여기에서는 전두엽 병변으로 인한 이서 장애, 실행실서증, 공간실서증을 살펴보고자 한다.

쓰기 집행 시 추상적인 철자 표상을 문자로 변환하기 위해서는, 특정한 서체나 대소문자의 글자 모양에 대한 접근, 그리고 글자 모양에 따른 운동프로그램에 대한 접근이 요구된다. 이처럼 자소-버퍼 단계에 임시로 저장된 철자의 물리적 글자 형태에 접근하는 이서 단계(allographic level)에서 결함이 발생한 실서증 유형을 이서 장애(allographic agraphia)라 한다. 이서 장애의 사례 중 일부 연구는 두정-후두 영역 또는 후두-측두 영역에서 이서 체계의 손상이 나타난다고 보고하였다(Black et al., 1989; De Bastiani & Barry, 1989; Menichelli et al., 2012). 이서 단계의 손상은 결과적으로, 적절한 형태의 자소를 선택하는 데 어려움이 발생하여 대소문자를 혼용해서 사용하는 오류가 발생하거나(De Bastiani & Barry, 1989; Forbes & Venneri, 2003), 특정한 글씨체의 쓰기를 손상시킬 수 있다(Destreri et al., 2000; Menichelli et al., 2012; Patterson & Wing, 1989; Richard Hanley & Peters, 2001; Silveri, 1996; Trojano & Chiacchio, 1994). 또한, 이서 장애 환자들은 구어 철자 능력과 시공간 능력이 보존되며 정상적인 글자 형태를 갖지만, 외형이 비슷한 다른 자소로 대체하는 오류가 빈번하게 발생한다(Di Pietro et al., 2011; Ellis, 1982). 이와 관련해서 Ellis(1982)는 구어 철자대기 능력이 보존된 상태에서 나타나는 자소의 대체 오류는 이서 단계의 표상과 자소-운동 코드(graphic motor codes) 간 매핑(mapping)의 어려움이 반영된다고 주장하였다.

한편, 좌측 또는 우측 전두엽 병변이 포함되거나(Maeda & Shiraishi, 2018; Menichelli et al., 2008; Richard Hanley & Peters, 2001), 뒤쪽 하전두엽, 전대상피질(anterior cingular cortex)과 내측전전두(medial prefrontal cortex) 영역 등의 전두엽에 한정된 병변의 사례가 보고되었다(Di Pietro et al., 2011; Hillis et al., 2004; Matiello et al., 2015). 앞서 BA 44, 45, 6에 동일한 병소를 가진 3명의 사례를 소개한 Hillis 등(2004)은 이들이 철자 어휘집에 대한 접근의 결함으로 나타나는 어휘실서증 양상 이외에, 자소의 표상을 글자의 특정 형태로 변환하는 과정의 기전이 BA 6에 있다고 주장하였다. 이들은 모두 대소문자의 변환 과제를 지연되게 수행하였으나 글자의 길이와 상관없이 오류를 보였고, 형태가 잘 갖추어진 글자를 산출하여 자소-버퍼나 실행실서증의 가능성을 배제하였다.

또한, Di Pietro 등(2011)은 대문자를 잘 쓰지 못하여 소문자로만 쓰는 양상을 보이는 대문자 특정적(capital letter-specific) 이서 장애 환자를 보고하였다. 이서 장애의 양상은 대문자와 소문자의 해리를 통해 관찰된 영어권 연구 이외에 일어권의 연구에서도 보고되었는데, Maeda와 Shiraishi(2018)는 두 가지 서체인 가타카나와 히라가나를 혼용하는 이서 장애 사례에서 신경전달물질의 균형을 회복시키는 약물(donepezil chloride)을 주입하였을 때 주의력이 향상되면서 이서 장애 증상이 호전되는 양상을 확인하였다. 따라서 이서 장애는 뇌의 국소적 병변에 의한 특정적 증상이라기보다 주의력과 같은 전반적인 인지기능의 저하에 기인할 수 있음을 역설하였다. 이렇듯 이서 체계의 기전으로 추정되는 영역은 일관적이지 않으며, 관련된 영역들의 관계가 명확하지 않음을 확인할 수 있다.

이서 단계에서 일시적인 철자의 표상을 해당되는 글자의 형태로 변환한 이후에는, 글자의 크기나 획의 순서와 같이 구체적인 요소들을 포함하여 글자를 쓰기 위한 운동 계획이 결합되어야 한다. 이러한 자소-운동 계획 단계의 결함으로 발생하는 실행실서증은 글쓰기의 운동 계획 장애로, 사지 실행증이나 다른 형태의 실서증 양상과 동반될 수 있으며, 단독으로 순수한 실행실서증이 나타나는 경우도 있다. 실행실서증은 일반적으로 관념운동 실행증의 한 형태로, 글자를 형성하는 데 있어 어려움을 보이며 글씨의 구성 자체가 불가능한 경우도 포함된다. 실행실서증은 두정엽의 병변, 주로 우세 손잡이 대측(Baxter & Warrington, 1986; Crary & Heilman, 1988; Margolin & Binder, 1984; Otsuki et al., 1999)의 상두정소엽(superior parietal lobe)에서 나타난다. 이러한 글자를 형성하고 구성하는 영역들이 손상되면, 자발적인 쓰기나 받아쓰기 과제 수행 시 알아볼 수 없는 글자를 산출하게 된다. 특히 획(stroke)이 생략 또는 추가되거나, 순서의 오류가 발생한다. 실행실서증 환자의 구어 철자대기 능력은 보존되며, 베껴쓰기 과제에서는 비교적으로 양호한 수행을 보인다.

이러한 양상은 전두엽 단독의 병변으로도 보고되었는데, 이들은 브로카 영역에 해당하는 BA 44, 45와 상전두이랑의 BA 6, 좌측 중심앞이랑(left precentral gyrus, BA 4)과 같은 영역의 손상으로 사지의 운동이 정상이며 다른 언어적인 결함이 없는 순수 실행실서증을 보였다(Anderson et al., 1990; Hodges, 1991; Jung et al., 2015; Klein et al., 2016; Kurosaki et al., 2016; Starrfelt, 2007). 좌측 중심앞이랑은 손의 움직임을 준비하고 집행하는 작업과 두정엽의 쓰기 운동 이미지를 전두엽의 운동프로그램으로 변환하는 작업과 관련이 있다(Kurosaki et al., 2016; Planton et al., 2013). 또한, 언어 처리에 핵심적인 브로카 영역도 마찬가지로 손의 움직임에 대한 심상이 이루어질 때 활성화되는 것으로 보고된다(Rizzolatti et al., 2002). 대뇌피질의 전기자극과 fMRI를 통해 쓰기 처리에 관여하는 전두엽 영역을 확인한 연구에 따르면, 상전두이랑 근처의 양측 BA 6영역은 손글씨 산출에 선택적으로 관여한다(Roux et al., 2009). 특히, 일차 운동 영역인 BA 4와 함께 중심앞이랑을 구성하며, 전운동영역으로써 측두-두정 연합 영역으로부터 전전두피질을 거쳐 처리된 감각 정보를 수용하고 통합한다. 엑스너 영역(Exner’s area)으로도 알려진 중전두이랑의 뒷부분은 브로카 영역의 위쪽에 위치하여 쓰기의 집행이 이루어지기 전까지 자소 표상 단계, 이서 단계, 그리고 자소에 대한 운동을 계획하는 단계까지 쓰기의 말초 처리 과정에서 다양한 기능을 담당하는 것으로 보인다(Hillis et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2015). 따라서 해당 영역의 손상은 활성화된 자소의 이미지의 정보를 자소운동양식(graphic motor pattern)으로 전달하는 데 어려움을 유발한다(Friedman & Alexander, 1989). Purcell 등(2011)은 엑스너 영역이 다양한 산출 양상(필기 혹은 타자치기)에서도 자소의 표상을 운동 명령으로 변환하는 역할을 맡는다고 주장하였다. 또한, 해당 영역은 글자와 아라비아 숫자의 받아쓰기 과제에서 각각 상종단다발과 하종단다발을 통한 활성화가 이루어지며, 다른 영역으로부터 전달받은 다양한 정보를 통합하여 쓰기 처리를 촉진시키는 역할을 수행하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Jung et al., 2015; Klein et al., 2016; Starrfelt, 2007).

글자나 단어를 제대로 된 형태로 쓰기 위해서는 공간 지각 능력과 상호작용하는 자소 산출 프로그래밍 체계를 통해 글자의 구성요소가 적절하게 배치되어야 한다. 이러한 기능의 결함은 장애의 양상에 따라 시공간실서증, 또는 구심(afferent)실서증으로 묘사된다(Ullrich & Roeltgen, 2012). 비우세 반구의 두정엽 손상으로 인한 공간실서증은 보통 편측 공간 무시 증후군이 동반되어, 병소의 동측 공간에만 자소를 산출하는 모습이 관찰된다. 또한, 획을 반복하거나, 수평으로 직선을 그리지 못하거나, 자소 사이에 빈 공간을 삽입하는 오류가 관찰된다(Ellis et al., 1987).

전두엽 병변에 국한된 공간실서증 연구는 극히 제한적이었는데, 비우세 반구의 전두엽 손상으로 공간실서증 양상이 보고되었다(Ardila & Rosselli, 1993). 이들은 두정엽 병변의 환자군과 비교하였을 때 상대적으로 경미한 실서증 양상을 보였으며, 글자 ‘n, m, u’와 숫자 ‘3’의 획을 연장하여 추가하거나, ‘olla’ 대신 ‘ollla’와 같이 글자를 반복하여 사용하는 운동 보속증에 가까운 양상을 나타냈다. 이는 일반적인 두정엽 병변으로 인한 공간실서증의 구성적 결함과는 구별된다.

3. 결론

전두엽은 언어, 인지, 운동과 같은 다양한 능력을 통합하고 처리하며 다른 영역과의 네트워크를 통해 조화로운 수행을 한다. 전두엽 손상에 기인한 실서증 연구의 결과를 종합하자면 다음과 같다. 먼저, 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정에서 전두엽은 철자 처리에 관여한다. 전두엽은 인지 제어 기능을 담당하기 때문에(Brass & von Cramon, 2002) 측두엽 또는 두정엽에서부터 출발하는 어휘 및 음운 경로를 통해 활성화된 철자를 산출하기 위한 과정을 조절한다(Bitan et al., 2005; Booth et al., 2002). 즉, 전두엽은 쓰기의 중추 처리 과정에서 철자 정보를 최종적으로 표현하기 위한 어휘의 선택이나 음운-철자 변환 시에 정확한 음소를 찾아내는 역할에 관여함을 시사한다. 다음으로, 전두엽은 중추 처리 과정에서 산출된 추상적인 철자 정보를 말초 처리 과정으로 전달하는 과정에서 운동 명령으로의 변환에 개입하며, 최종적으로는 운동 계획, 실행 및 조절을 통한 글자의 물리적 산출을 담당한다.

이렇듯 전두엽이 다양한 역할을 통해 다방면적으로 개입하고 있음에도 불구하고 그간 쓰기 처리 과정에서의 전두엽의 역할은 상대적으로 주목받지 못하였다. 따라서 본 문헌 검토를 통하여 전두엽에 국한된 병소로 인한 실서증의 특성을 고찰하고 정리하였다는 것에 본 연구의 의의가 있다. 이는 임상에서 전두엽 손상으로 나타나는 쓰기 오류에 대한 양상 확인과 더불어 실서증에 대한 감별 진단 시 활용될 수 있는 기초 자료로 활용될 수 있을 것이다. 비록 일부 단계에서는 제한된 사례로 인하여 그 결과를 일반화하거나 단정하기에는 어려움이 있다. 또한, 선정된 문헌 중 일부에서는 자세한 뇌 영상 자료를 제공하지 못하거나, 병변에 대한 판독 기록에 의존하여 해석하였기 때문에 병변과의 상관성에 대한 분석이 이루어지지 못하였다. 추후에는 본 문헌 고찰에 기반하여 상대적으로 주목받지 못했던 전두엽 손상으로 인한 중추형 실서증 특성을 살펴보는 연구가 활발히 진행될 수 있기를 기대한다.

Acknowledgments

이 논문은 2021년도 정부(교육부)의 재원으로 한국연구재단의 지원을 받아 수행된 기초연구사업임(No. 2021R1I1A2044504).

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. 2021R1I1A2044504).

References

-

Abe, K., & Yokoyama, R. (1994). A selective agraphia of Kana. Behavioural Neurology, 7(2), 79–81.

[https://doi.org/10.3233/BEN-1994-7205]

-

Alexander, M. P., Friedman, R. B., Loverso, F., & Fischer, R. S. (1992). Lesion localization of phonological agraphia. Brain and Language, 43(1), 83-95.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(92)90022-7]

-

Anderson, S. W., Damasio, A. R., & Damasio, H. (1990). Troubled letters but not numbers: Domain specific cognitive impairments following focal damage in frontal cortex. Brain, 113(3), 749-766.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/113.3.749]

-

Ardila, A., & Rosselli, M. (1993). Spatial agraphia. Brain and Cognition, 22(2), 137-147.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/brcg.1993.1029]

-

Arroyo-Anlló, E. M., Pluchon, C., Bouyer, C., Baudiffier, V., Stal, V., Du Boisgueheneuc, F., . . . Gil, R. (2023). A crossed pure agraphia by graphemic buffer impairment following right orbito-frontal glioma resection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1346.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021346]

-

Baddeley, A. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(11), 417-423.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01538-2]

-

Baxter, D. M., & Warrington, E. K. (1986). Ideational agraphia: A single case study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 49(4), 369-374.

[https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.49.4.369]

-

Beauvois, M. F., & Dérouesné, J. (1981). Lexical or orthographic agraphia. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 104(Pt 1), 21-49.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/104.1.21]

-

Beeson, P. M., Hirsch, F. M., & Rewega, M. A. (2002). Successful single-word writing treatment: Experimental analyses of four cases. Aphasiology, 16(4-6), 473-491.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030244000167]

-

Bitan, T., Booth, J. R., Choy, J., Burman, D. D., Gitelman, D. R., & Mesulam, M.-M. (2005). Shifts of effective connectivity within a language network during rhyming and spelling. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(22), 5397-5403.

[https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0864-05.2005]

-

Black, S. E., Behrmann, M., Bass, K., & Hacker, P. (1989). Selective writing impairment: Beyond the allographic code. Aphasiology, 3(3), 265-277.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038908248994]

-

Booth, J. R., Burman, D. D., Meyer, J. R., Gitelman, D. R., Parrish, T. B., & Mesulam, M. M. (2002). Functional anatomy of intra- and cross-modal lexical tasks. NeuroImage, 16(1), 7-22.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2002.1081]

-

Bormann, T., Wallesch, C.-W., & Blanken, G. (2008). “Fragment errors” in deep dysgraphia: Further support for a lexical hypothesis. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 25(5), 745-764.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290802315834]

-

Brass, M., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2002). The role of the frontal cortex in task preparation. Cerebral Cortex, 12(9), 908-914.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/12.9.908]

-

Bub, D., & Kertesz, A. (1982). Deep agraphia. Brain and Language, 17(1), 146-165.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(82)90011-6]

-

Burton, M. W., Small, S. L., & Blumstein, S. E. (2000). The role of segmentation in phonological processing: An fMRI investigation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(4), 679-690.

[https://doi.org/10.1162/089892900562417]

-

Caramazza, A., & Miceli, G. (1991). Selective impairment of thematic role assignment in sentence processing. Brain and Language, 41(3), 402-436.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(91)90164-v]

-

Caramazza, A., Miceli, G., Villa, G., & Romani, C. (1987). The role of the graphemic buffer in spelling: Evidence from a case of acquired dysgraphia. Cognition, 26(1), 59-85.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(87)90015-4]

- Carlson, N. R. (2007). Physiology of behavior (9th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

-

Catani, M., Mesulam, M. M., Jakobsen, E., Malik, F., Martersteck, A., Wieneke, C., . . . Rogalski, E. (2013). A novel frontal pathway underlies verbal fluency in primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 136(8), 2619-2628.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt163]

-

Chayer, C., & Freedman, M. (2001). Frontal lobe functions. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 1(6), 547-552.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-001-0060-4]

-

Cloutman, L., Gingis, L., Newhart, M., Davis, C., Heidler-Gary, J., Crinion, J., & Hillis, A. E. (2009). A neural network critical for spelling. Annals of Neurology, 66(2), 249-253.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21693]

-

Code, C., Tree, J. J., & Mariën, P. (2017). Squaring the round: An unusual progressive graphomotor impairment with post-mortem findings. Journal of Neuropsychology, 11(2), 222-237.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/jnp.12083]

-

Crary, M. A., & Heilman, K. (1988). Letter imagery deficits in a case of pure apraxic agraphia. Brain and Language, 34(1), 147-156.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(88)90126-3]

-

Croisile, B., Laurent, B., Michel, D., & Trillet, M. (1990). Pure agraphia after deep left hemisphere haematoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 53(3), 263-265.

[https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.53.3.263]

- Croisile, B., Trillet, M., Laurent, B., Latombe, D., & Schott, B. (1989). Agraphie lexicale par hématome temporo-pariétal gauche. Revue Neurologique (Paris), 145(4), 287-292.

-

Cubelli, R. (1991). A selective deficit for writing vowels in acquired dysgraphia. Nature, 353(6341), 258-260.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/353258a0]

-

De Bastiani, P., & Barry, C. (1989). A cognitive analysis of an acquired dysgraphic patient with an “allographic” writing disorder. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 6(1), 25-41.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643298908253283]

-

Deldar, Z., Gevers-Montoro, C., Khatibi, A., & Ghazi-Saidi, L. (2021). The interaction between language and working memory: A systematic review of fMRI studies in the past two decades. AIMS Neuroscience, 8(1), 1-32.

[https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2021001]

-

Démonet, J.-F., Price, C., Wise, R., & Frackowiak, R. S. J. (1994). A PET study of cognitive strategies in normal subjects during language tasks: Influence of phonetic ambiguity and sequence processing on phoneme monitoring. Brain, 117(4), 671-682.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/117.4.671]

-

De Partz, M. P., Lochy, A., & Pillon, A. (2005). Multiple levels of letter representation in written spelling: Evidence from a single case of dysgraphia with multiple deficits. Behavioural Neurology, 16(2-3), 119-144.

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2005/821734]

-

Destreri, N. D. G., Farina, E., Alberoni, M., Pomati, S., Nichelli, P., & Mariani, C. (2000). Selective uppercase dysgraphia with loss of visual imagery of letter forms: A window on the organization of graphomotor patterns. Brain and Language, 71(3), 353-372.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/brln.1999.2263]

-

Di Pietro, M., Schnider, A., & Ptak, R. (2011). Peripheral dysgraphia characterized by the co-occurrence of case substitutions in uppercase and letter substitutions in lowercase writing. Cortex, 47(9), 1038-1051.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2010.11.005]

- Ellis, A. W. (1982). Spelling and writing (and reading and speaking). In Normality and pathology in cognitive functions (pp. 113-146). London: Academic Press.

-

Ellis, A. W., Young, A. W., & Flude, B. M. (1987). “Afferent dysgraphia” in a patient and in normal subjects. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 4(4), 465-486.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643298708252048]

-

Forbes, K. E., & Venneri, A. (2003). A case for case: Handling letter case selection in written spelling. Neuropsychologia, 41(1), 16-24.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00139-9]

-

Friedman, R. B., & Alexander, M. P. (1989). Written spelling agraphia. Brain and Language, 36(3), 503-517.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(89)90079-3]

- González-Fernández, M., & Hillis, A. E. (2018). Language and the frontal cortex. In B. L. Miller & J. L. Cummings (Eds.), The human frontal lobes: Functions and disorders (3rd ed., pp. 158-170). New York: The Guilford Press.

-

Hagtvet, B. E. (1993). From oral to written language: A developmental and interventional perspective. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 8(3), 205-220.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03174080]

-

Hatfield, F. M., & Patterson, K. E. (1983). Phonological spelling. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 35(3), 451-468.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14640748308402483]

-

Hillis, A. E., & Caramazza, A. (1989). The graphemic buffer and attentional mechanisms. Brain and Language, 36(2), 208-235.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(89)90061-6]

-

Hillis, A. E., Chang, S., Breese, E., & Heidler, J. (2004). The crucial role of posterior frontal regions in modality specific components of the spelling process. Neurocase, 10(2), 175-187.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13554790409609947]

-

Hillis, A. E., Rapp, B. C., & Caramazza, A. (1999). When a rose is a rose in speech but a tulip in writing. Cortex, 35(3), 337-356.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70804-9]

-

Hillis, A. E., Wityk, R. J., Barker, P. B., & Caramazza, A. (2003). Neural regions essential for writing verbs. Nature Neuroscience, 6(1), 19-20.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nn988]

-

Hodges, J. R. (1991). Pure apraxic agraphia with recovery after drainage of a left frontal cyst. Cortex, 27(3), 469-473.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80045-0]

-

Jung, S., Halm, K., Huber, W., Willmes, K., & Klein, E. (2015). What letters can “learn” from Arabic digits-fMRI-controlled single case therapy study of peripheral agraphia. Brain and Language, 149, 13-26.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2015.07.004]

-

Keller, C., & Meister, I. G. (2014). Agraphia caused by an infarction in Exner’s area. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 21(1), 172-173.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2013.02.015]

-

Klein, E., Willmes, K., Jung, S., Huber, S., Braga, L. W., & Moeller, K. (2016). Differing connectivity of Exner’s area for numbers and letters. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 281.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00281]

-

Kurosaki, Y., Hashimoto, R., Tatsumi, H., & Hadano, K. (2016). Pure agraphia after infarction in the superior and middle portions of the left precentral gyrus: Dissociation between Kanji and Kana. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 26, 150-152.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2015.07.026]

-

Lesser, R. (1990). Superior oral to written spelling: Evidence for separate buffers? Cognitive Neuropsychology, 7(4), 347-366.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643299008253446]

-

Levy, D. F., Silva, A. B., Scott, T. L., Liu, J. R., Harper, S., Zhao, L., . . . Chang, E. F. (2023). Apraxia of speech with phonological alexia and agraphia following resection of the left middle precentral gyrus: Illustrative case. Journal of Neurosurgery: Case Lessons, 5(13), CASE22504.

[https://doi.org/10.3171/case22504]

-

Linebarger, M. C., Schwartz, M. F., Romania, J. R., Kohn, S. E., & Stephens, D. L. (2000). Grammatical encoding in aphasia: Evidence from a “processing prosthesis”. Brain and Language, 75(3), 416-427.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/brln.2000.2373]

-

Luzzi, S., & Piccirilli, M. (2003). Slowly progressive pure dysgraphia with late apraxia of speech: A further variant of the focal cerebral degeneration. Brain and Language, 87(3), 355-360.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00134-2]

-

Maeda, K., & Shiraishi, T. (2018). Revival of historical Kana orthography in a patient with allographic agraphia. Internal Medicine, 57(5), 745-750.

[https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.9368-17]

-

Maeda, K., Shiraishi, T., & Idehara, R. (2015). Agraphia in mobile text messages in a case of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with frontotemporal dementia. Internal Medicine, 54(23), 3065-3068.

[https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4982]

-

Maeshima, S., Sekiguchi, E., Kakishita, K., Okada, H., Okita, R., Ozaki, F., & Moriwaki, H. (2003). Agraphia with abnormal writing stroke sequences due to cerebral infarction. Brain Injury, 17(4), 339-345.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0269905021000038374]

-

Margolin, D. I., & Binder, L. (1984). Multiple component agraphia in a patient with atypical cerebral dominance: An error analysis. Brain and Language, 22(1), 26-40.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(84)90077-0]

-

Marien, P., Pickut, B. A., Engelborghs, S., Martin, J.-J., & De Deyn, P. P. (2001). Phonological agraphia following a focal anterior insulo-opercular infarction. Neuropsychologia, 39(8), 845-855.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00003-6]

-

Martin, R. C., & Blossom-Stach, C. (1986). Evidence of syntactic deficits in a fluent aphasic. Brain and Language, 28(2), 196-234.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(86)90101-7]

-

Matiello, M., Zimmerman, E., Caplan, D., & Cohen, A. B. (2015). Reversible cursive agraphia. Neurology, 85(3), 295-296.

[https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001766]

-

Menichelli, A., Machetta, F., Zadini, A., & Semenza, C. (2012). Allographic agraphia for single letters. Behavioural Neurology, 25(3), 233-244.

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/796304]

-

Menichelli, A., Rapp, B., & Semenza, C. (2008). Allographic agraphia: A case study. Cortex, 44(7), 861-868.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2007.07.004]

-

Miceli, G., Capasso, R., Ivella, A., & Caramazza, A. (1997). Acquired dysgraphia in alphabetic and stenographic handwriting. Cortex, 33(2), 355-367.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70011-X]

-

Miceli, G., Silveri, M. C., Romani, C., & Caramazza, A. (1989). Variation in the pattern of omissions and substitutions of grammatical morphemes in the spontaneous speech of so-called agrammatic patients. Brain and Language, 36(3), 447-492.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(89)90076-8]

-

Nolan, K. A., & Caramazza, A. (1982). Modality-independent impairments in word processing in a deep dyslexic patient. Brain and Language, 16(2), 237-264.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(82)90086-5]

-

Otsuki, M., Soma, Y., Arai, T., Otsuka, A., & Tsuji, S. (1999). Pure apraxic agraphia with abnormal writing stroke sequences: Report of a Japanese patient with a left superior parietal haemorrhage. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 66(2), 233-237.

[https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.66.2.233]

-

Patterson, K. (1986). Lexical but nonsemantic spelling? Cognitive Neuropsychology, 3(3), 341-367.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643298908253282]

-

Patterson, K., & Wing, A. M. (1989). Processes in handwriting: A case for case. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 6(1), 1-23.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643298908253282]

-

Piccirilli, M., Petrillo, S., & Poli, R. (1992). Dysgraphia and selective impairment of the graphemic buffer. The Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 13(2), 113-117.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02226964]

-

Planton, S., Jucla, M., Roux, F.-E., & Démonet, J.-F. (2013). The “handwriting brain”: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies of motor versus orthographic processes. Cortex, 49(10), 2772-2787.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2013.05.011]

-

Posteraro, L., Zinelli, P., & Mazzucchi, A. (1988). Selective impairment of the graphemic buffer in acquired dysgraphia: A case study. Brain and Language, 35(2), 274-286.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(88)90111-1]

-

Purcell, J. J., Turkeltaub, P. E., Eden, G. F., & Rapp, B. (2011). Examining the central and peripheral processes of written word production through meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 239.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00239]

-

Rapcsak, S. Z., Arthur, S. A., & Rubens, A. B. (1988). Lexical agraphia from focal lesion of the left precentral gyrus. Neurology, 38(7), 1119.

[https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.38.7.1119]

-

Rapcsak, S. Z., Arthur, S. A., Bliklen, D. A., & Rubens, A. B. (1989). Lexical agraphia in Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Neurology, 46(1), 65-68.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1989.00520370067018]

-

Rapp, B., & Dufor, O. (2011). The neurotopography of written word production: An fMRI investigation of the distribution of sensitivity to length and frequency. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(12), 4067-4081.

[https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00109]

-

Richard Hanley, J., & Peters, S. (2001). Allograph errors and impaired access to graphic motor codes in a case of unilateral agraphia of the dominant left hand. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 18(4), 307-321.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290126134]

-

Rizzolatti, G., Fogassi, L., & Gallese, V. (2002). Motor and cognitive functions of the ventral premotor cortex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 12(2), 149-154.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00308-2]

-

Roeltgen, D. P., & Heilman, K. M. (1984). Lexical agraphia: Further support for the two-system hypothesis of linguistic agraphia. Brain, 107(3), 811-827.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/107.3.811]

-

Roeltgen, D. P., & Heilman, K. M. (1985). Review of agraphia and a proposal for an anatomically-based neuropsychological model of writing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 6(3), 205-229.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716400006184]

- Roeltgen, D. P., & Rapcsak, S. Z. (1993). Acquired disorders of writing and spelling. In G. Blanken, J. Dittmann, H. Grimm, J. C. Marshall, & C.-W. Wallesch (Eds.), Linguistic disorders and pathologies (pp. 262-278). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

-

Romine, C. B., & Reynolds, C. R. (2004). Sequential memory: A developmental perspective on its relation to frontal lobe functioning. Neuropsychology Review, 14(1), 43-64.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/b:nerv.0000026648.94811.32]

-

Rothi, L. J. G., Roeltgen, D. P., & Kooistra, C. A. (1987). Isolated lexical agraphia in a right-handed patient with a posterior lesion of the right cerebral hemisphere. Brain and Language, 30(1), 181-190.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(87)90137-1]

-

Roux, F.-E., Dufor, O., Giussani, C., Wamain, Y., Draper, L., Longcamp, M., & Démonet, J.-F. (2009). The graphemic / motor frontal area Exner’s area revisited. Annals of Neurology, 66(4), 537-545.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21754]

-

Sakurai, Y., Furukawa, E., Kurihara, M., & Sugimoto, I. (2018). Frontal phonological agraphia and acalculia with impaired verbal short-term memory due to left inferior precentral gyrus lesion. Case Reports in Neurology, 10(1), 72-82.

[https://doi.org/10.1159/000487847]

-

Sakurai, Y., Matsumura, K., Iwatsubo, T., & Momose, T. (1997). Frontal pure agraphia for Kanji or Kana: Dissociation between morphology and phonology. Neurology, 49(4), 946-952.

[https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.49.4.946]

-

Shallice, T. (1981). Phonological agraphia and the lexical route in writing. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 104(3), 413-429.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/104.3.413]

-

Shapiro, K. A., Pascual-Leone, A., Mottaghy, F. M., Gangitano, M., & Caramazza, A. (2001). Grammatical distinctions in the left frontal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 13(6), 713-720.

[https://doi.org/10.1162/089892901750363235]

-

Silveri, M. C. (1996). Peripheral aspects of writing can be differentially affected by sensorial and attentional defect: Evidence from a patient with afferent dysgraphia and case dissociation. Cortex, 32(1), 155-172.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-9452(96)80022-7]

-

Starrfelt, R. (2007). Selective alexia and agraphia sparing numbers—A case study. Brain and Language, 102(1), 52-63.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2007.01.005]

- Swinney, D., Prather, P., & Love, T. (2000). The time-course of lexical access and the role of context: Converging evidence from normal and aphasic processing. In Y. Grodzinsky, L. P. Shapiro, & D. Swinney (Eds.), Language and the brain: Representation and processing (pp. 273-292). San Diego: Academic Press.

-

Tainturier, M. J., & Rapp, B. C. (2004). Complex graphemes as functional spelling units: Evidence from acquired dysgraphia. Neurocase, 10(2), 122-131.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13554790490495096]

- Thompson, C. K., Faroqi-Shah, Y., & Lee, J. (2015). Models of sentence production. In A. E. Hillis (Ed.), The handbook of adult language disorders (2nd ed., pp. 328-354). New York: Psychology Press.

-

Tohgi, H., Saitoh, K., Takahashi, S., Takahashi, H., Utsugisawa, K., Yonezawa, H., . . . Sasaki, T. (1995). Agraphia and acalculia after a left prefrontal (F1, F2) infarction. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 58(5), 629-632.

[https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.58.5.629]

-

Trojano, L., & Chiacchio, L. (1994). Pure dysgraphia with relative sparing of lower-case writing. Cortex, 30(3), 499-507.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80844-0]

- Ullrich, L., & Roeltgen, D. P. (2012). Agraphia. In K. M. Heilman & E. Valenstein (Eds.), Clinical neuropsychology (5th ed., pp. 130-151). New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Utianski, R. L., Duffy, J. R., Savica, R., Whitwell, J. L., Machulda, M. M., & Josephs, K. A. (2018). Molecular neuroimaging in primary progressive aphasia with predominant agraphia. Neurocase, 24(2), 121-123.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2018.1477733]

-

Zatorre, R. J., Evans, A. C., Meyer, E., & Gjedde, A. (1992). Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science, 256(5058), 846-849.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1589767]

-

Zatorre, R. J., Meyer, E., Gjedde, A., & Evans, A. C. (1996). PET studies of phonetic processing of speech: review, replication, and reanalysis. Cerebral Cortex, 6(1), 21-30.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/6.1.21]

- Zurif, E., & Swinney, D. (1994). The neuropsychology of language. In M. A. Gernsbacher (Ed.), Handbook of psycholinguistics (pp. 1055-1074). San Diego: Academic Press.